(October 18, 2020)

The field of genetic genealogy is a fascinating one, but it can also be complex and confusing, especially for those just getting started, many of whom would likely be my readers when my newest book, Finding Sisters, gets published. I was still just barely more than a novice myself when I started the project, though I eventually found what I was looking for (with lots of generous assistance from others more experienced than I), and I wanted to share that story with others in a way that would encourage them to get involved in their own genetic history while not downplaying the complexities of the journey or throwing the shade of discouragement on anyone who felt confused by all the details that are a necessary part of the search for genetic ancestry.

Because mine was a story with a clear beginning, middle, and end, I started to write about the details in chronological order, and because I had been saving absolutely everything from the very beginning of my explorations (emails, documents, photos, notes from conversations, relationship charts, family trees, etc.), this meant going back over what had happened along the way in minute detail. This kept me honest about what had taken place and when, and it was also a great way to refresh my own memory about how everything had unfolded. In the excitement of the discovery process, it had been easy to conflate the details, to mix up how and when certain things had occurred, and to forget certain important elements of the story.

As I started to present the developing chapters to the women in my writing group, two issues became very clear. First, the scientific details and all the family names were confusing to someone who was not directly engaged in the search, even when they were interested in the story. I was fascinated with what I was discovering, but my audience was mostly just bewildered and kept losing the narrative thread. This was the proverbial problem of not being able to see the forest for all the trees. One of the first things I needed to do, then, was to limit my use of the technical language in the story itself (footnotes became my good friend, so I could include the technical details for those who might want them but without impeding the narrative through line). Another was to consider visual aids in the form of relationship charts and/or developing family trees at various points in the story to help the reader understand the intricate web of relationships that was unfolding.

This is what I eventually discovered about my birth mother, her relationships with various men, and her other children, my maternal half-siblings, two of whom were deceased long before I knew who they were. Because the file is a pdf, which is not supported as an available image in WordPress, this is a screenshot of the file that will become an illustration in the book itself.

The other complexity was the incredible number of names involved in a genealogical research project. If anyone has ever done a family tree for the family members they already know about, it’s crammed with surnames, often different within every generation due to marriages, blended families, and the like. And for the adoptee, this is even more complicated because all the family names we might know from our own growing up usually have nothing at all to do with those in our genetic lineage. As well, some of my extended genetic family members were not interested in being linked to me, the illegitimate outsider, according to some friendlier folks I encountered along the way. I solved this twofold problem by eliminating surnames in the story I was telling. Most people can easily keep track of multiple characters by first names, so that’s the route I chose to write about my genetic families on both sides, maternal and paternal. According to the ever-astute members of my writing group, not knowing the surnames did not distract from the primary account of finding my two living half-sisters and sharing more about the family backgrounds of both my genetic parents.

As I continued to share my experiences with the writing group, it became clear that the story was just as much about my developing relationship with my Swedish search angel, Thomas, as it was about my genetic family. Thomas was distant part of that family (a maternal sixth cousin as it turned out), but that didn’t become clear until well into the adventure. So instead of simply being a friendly technical facilitator for my unfolding narrative, Thomas eventually became a fully fleshed out character (as full as possible for someone you’ve never met in person, that is) and an important part of the story.

One of the other things that those who heard my story along the way valued was the occasional photo that had come my way from extended family members or other sources. These photos helped my audience to define and identify with my genetic parents and other family members. Because I had her name early in the search process, I was able to get her photo from my birth mother’s high school yearbook, and once I contacted members of her family, finding other photos was simple because they were happy to share. Finding images of my birth father was much more difficult, especially since his name was one of the last ones I was able to uncover. But once the connection had been confirmed, extended family members were pleased to be able to share the images they had with me, though because he had died so young, there weren’t too many of them available. The photos below are what my parents would have looked like in the summer of 1948 when I was conceived while they were dating.

I presented my chapters to the writing group two separate times over the nearly two years that I worked on the manuscript: first drafts and then, after addressing the first set of comments, I shared the revised drafts a second time, which gave me a chance to revise a second time. All these revisions took place before I submitted the manuscript to the publisher for a possible contract, which happened just a month before the covid-19 shutdown in March 2020, and I signed my contract with the publisher in May. At the moment, I’m still sitting in the queue of books to be edited at Sunbury Press, but I expect to start working with the editor they will assign to me when I get to the head of the line fairly soon.

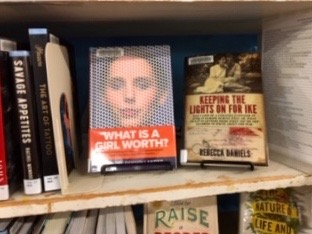

In the meantime, I’m working on recording the audiobook version of Keeping the Lights on for Ike and working on new writing. So, what’s next for this writer? Perhaps a more traditional memoir is in store. I’ll write about that next time. And hopefully about the process of working with my editor on Finding Sisters.